ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

on Jan 18, 2023 at 4:53 pm

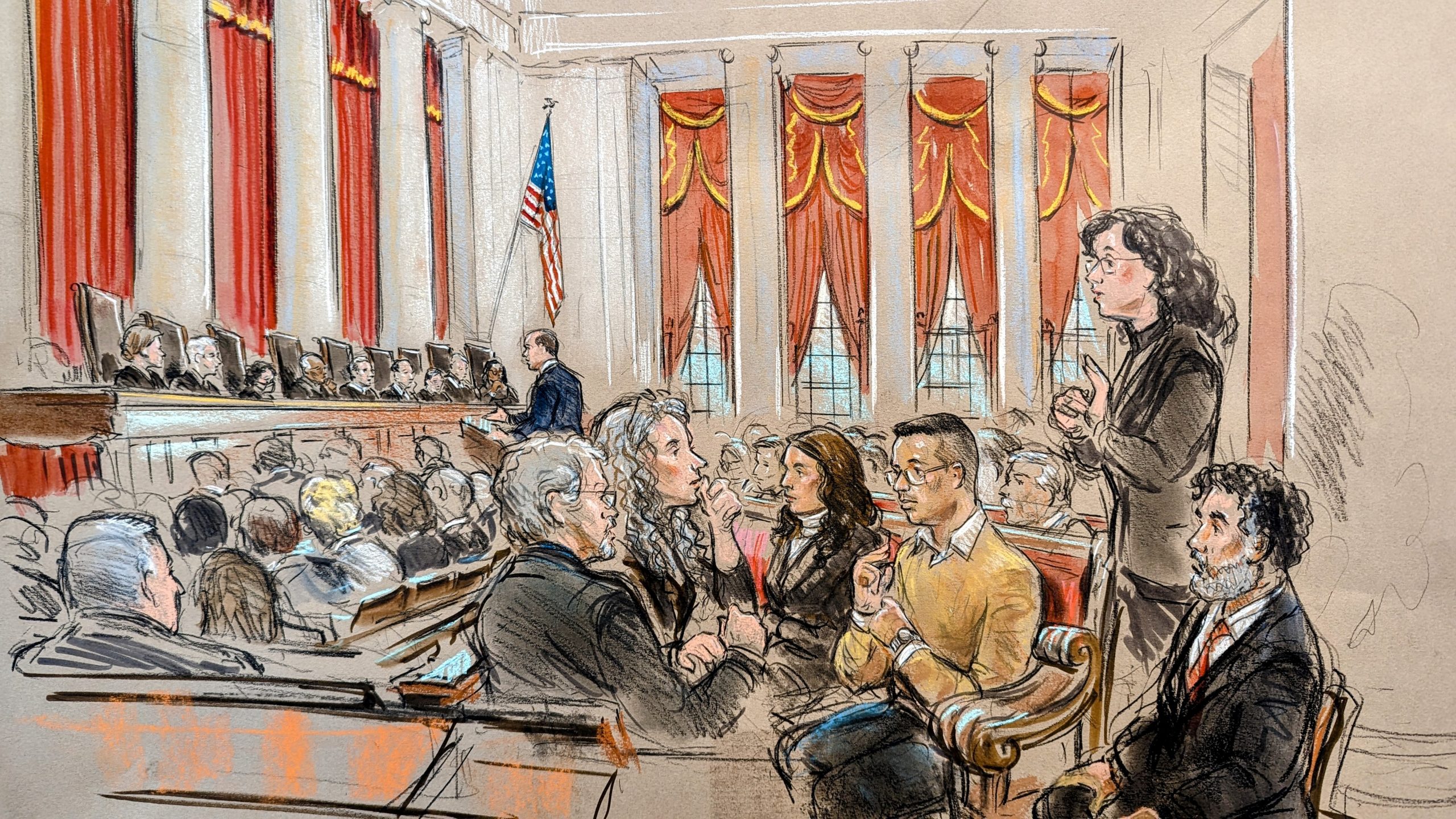

Plaintiff Miguel Perez, accompanied by sign-language interpreters, attends oral argument on Wednesday. His lawyer, Roman Martinez, speaks at the lectern. (William Hennessy)

The Supreme Court on Wednesday seemed ready to side with a deaf student who is seeking financial compensation from a Michigan school district that failed to provide him with a qualified sign-language interpreter.

The student, Miguel Perez, alleges that the school district violated the Americans with Disabilities Act. Lower courts threw out his lawsuit, ruling that a different federal law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, required him to “exhaust” his claims against the district – that is, fully pursue them in administrative proceedings before going to federal court. During over an hour of debate on Wednesday, however, a majority of the justices seemed inclined to allow Perez’s lawsuit to go forward.

Representing Perez, lawyer Roman Martinez stressed that for over 12 years, the Sturgis Public Schools “neglected Miguel, denied him an education, and lied to his parents about the progress he was allegedly making in school.” That “shameful conduct,” Martinez said, “permanently stunted Miguel’s ability to communicate with the outside world.”

Perez initially brought claims under both the ADA and the IDEA through state administrative channels. An administrative judge threw out the ADA claim on the ground that he lacked authority to hear it, and Perez reached a settlement with the school district on the IDEA claim. Perez then tried to revive the ADA claim in federal court.

The school district now argues that Perez’s IDEA settlement “extinguishes” Perez’s right to seek financial compensation under the ADA, Martinez said. “But Congress,” he continued, “didn’t punish kids for saying yes to favorable IDEA settlements.”

Representing the Sturgis Public Schools, lawyer Shay Dvoretzky countered that the primary purpose of the IDEA is to ensure that all students receive the education to which they are entitled. The IDEA’s exhaustion requirement, Dvoretzky insisted, simply channels all claims through the administrative procedures first, rather than allowing parents to go straight to court.

Shay Dvoretzky argues for Sturgis Public Schools. (William Hennessy)

Justice Elena Kagan proved to be one of Perez’s strongest supporters. Martinez, she told Dvoretzky, said that Perez had done “everything right,” and it’s “hard for me to see how that’s not true.”

Kagan pressed Dvoretzky to explain what else, in the school district’s view, Perez could have done to preserve his ADA claim. When Dvoretzky responded that Perez could have negotiated a settlement that included financial compensation for his ADA claim, Kagan was skeptical. Perez, she suggested, effectively had only two choices: reject the proposed settlement, which included an offer to pay for him to attend the Michigan School for the Deaf, or give up on the possibility of receiving compensation for the school district’s violations of the ADA.

Dvoretzky observed that, regardless of whether the court sides with the school district or with Perez, the prevailing party could try to use its leverage to extract favorable concessions from the other side in settlement negotiations. But he suggested that a ruling for the school district would make more sense as a practical matter, because a district has “an interest in trying to provide” a suitable education as soon as possible, and therefore will be more likely to reach a settlement. “It’s not in a school district’s interest,” he concluded, “to say we’re going to hold” the student’s education “hostage.”

But Kagan bridled at that suggestion. “It strikes me,” she told Dvoretzky, “that actually it’s the parents that have the greater incentive to get the education fixed for their child.” Special-education litigation, she continued, isn’t “being run by a lot of rapacious lawyers. This is litigation run by parents who are trying to do right by their kids.”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was similarly unpersuaded by the district’s arguments. In her view, “Congress was trying to make clear” with the text of the IDEA that “they did not want all claims arising out of these circumstances” to have to go through the entire set of administrative proceedings when a family is seeking relief, such as financial compensation, that is not available at all under the IDEA.

Several of the court’s conservative justices also appeared inclined to support Perez. Justice Clarence Thomas, who often asks the first question at each argument, quickly made clear where he stood. “I don’t even understand the use of the term ‘exhaustion’ here,” Thomas said, because the IDEA and the ADA involve “an entirely different remedy.”

Questions from Justice Amy Coney Barrett signaled that she too was sympathetic to Perez’s plight. She observed that if Perez had turned down the school district’s settlement offer and instead continue to litigate his IDEA claims so that he could preserve his right to bring his ADA claim later, he would risk losing his right to have the district reimburse his attorney’s fees, because those fees are not available to families that reject reasonable settlement offers.

Justice Samuel Alito displayed the strongest support for the school district’s position. He pushed back against Perez’s contention that the IDEA requires plaintiffs to exhaust their claims before going to federal court only when their lawsuit seeks the same relief that would be available under the IDEA. Although Perez argued that his lawsuit under the ADA seeks financial compensation, which is not available under the IDEA, Alito offered another reading of the IDEA. Perez’s lawsuit in federal court can be construed as seeking the same relief that would be available under the IDEA, he posited, if the term “relief” instead means “relief for the denial of” an appropriate education – which, Perez has conceded, is also the core of Perez’s ADA claims.

But Barrett pointed out that an ADA claim based only on the denial of an appropriate education could not go forward in any event. In Perez’s case, she emphasized, he had included “claims for emotional distress and other sorts of compensatory relief” in his complaint.

Anthony Yang, the assistant to the U.S. solicitor general who argued on behalf of the Biden administration in support of Perez, agreed, and it appeared that a majority of Barrett’s colleagues were likely to do so as well.