WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court announced on Thursday that it would hear a case that could radically reshape how federal elections are conducted by giving state legislatures independent power, not subject to review by state courts, to set election rules in conflict with state constitutions.

The case has the potential to affect many aspects of the 2024 election, including by giving the justices power to influence the presidential race if disputes arise over how state courts interpret state election laws.

In taking up the case, the court could upend nearly every facet of the American electoral process, allowing state legislatures to set new rules, regulations and districts on federal elections with few checks against overreach, and potentially create a chaotic system with differing rules and voting eligibility for presidential elections.

“The Supreme Court’s decision will be enormously significant for presidential elections, congressional elections and congressional district districting,” said J. Michael Luttig, a former federal appeals court judge. “And therefore, for American democracy.”

Protections against partisan gerrymandering established through the state courts could essentially vanish. The ability to challenge new voting laws at the state level could be reduced. And the theory underpinning the case could open the door to state legislatures sending their own slates of electors.

It is one thing to agree to hear a case, of course, and another to rule on it. But four justices have already expressed at least tentative support for the doctrine, making a decision accepting it more than plausible. The court will probably hear arguments in the fall and issue its decision next year.

Currently, Republicans have complete control over 30 state legislatures, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, and were the force behind a wave of new voting restrictions passed last year. And Republican legislatures in key battleground states like Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and North Carolina have used their control over redistricting to effectively lock in power for a decade.

Democrats, in turn, control just 17 state legislatures.

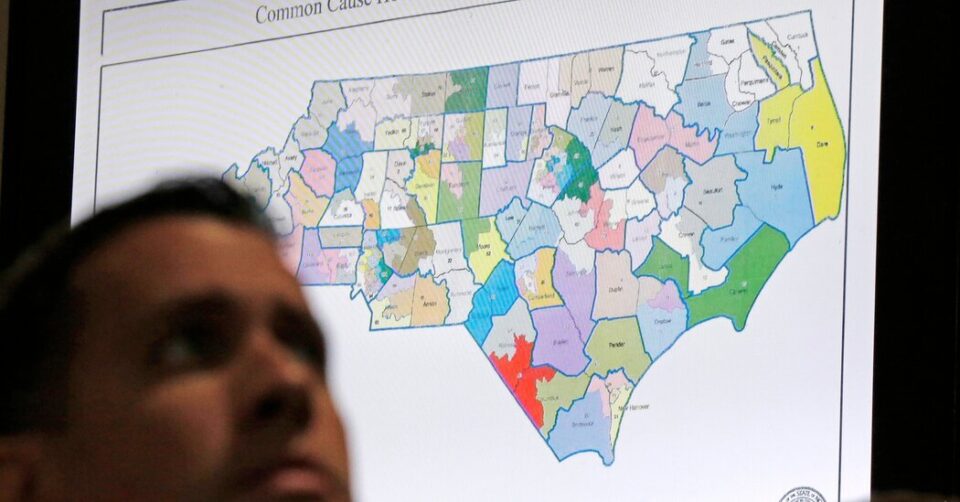

The case concerns a voting map drawn by the North Carolina legislature that was rejected as a partisan gerrymander by the State Supreme Court. Republicans seeking to restore the legislative map argued that the state court was powerless to act under the so-called independent state legislature doctrine.

The doctrine is based on a reading of two similar provisions of the U.S. Constitution. The one at issue in the North Carolina case, the Elections Clause, says: “The times, places and manner of holding elections for senators and representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof.”

That means, North Carolina Republicans argued, that the state legislature has sole responsibility among state institutions for drawing congressional districts and that state courts have no role to play.

The North Carolina Supreme Court rejected the argument that it was not entitled to review the actions of the state legislature, saying that would be “repugnant to the sovereignty of states, the authority of state constitutions and the independence of state courts, and would produce absurd and dangerous consequences.”

In an earlier encounter with the case in March, when the challengers unsuccessfully sought emergency relief, three members of the U.S. Supreme Court said they would have granted the application.

“This case presents an exceptionally important and recurring question of constitutional law, namely, the extent of a state court’s authority to reject rules adopted by a state legislature for use in conducting federal elections,” Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil M. Gorsuch.

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh agreed that the question was important. “The issue is almost certain to keep arising until the court definitively resolves it,” he wrote.

But the court should consider it in an orderly fashion, he wrote, outside the context of an approaching election. He wrote that the court should grant a petition seeking review on the merits “in an appropriate case — either in this case from North Carolina or in a similar case from another state.”

The court has now granted the petition in the North Carolina case, Moore v. Harper, No. 21-1271.

Some precedents of the U.S. Supreme Court tend to undermine the independent state legislature doctrine.

When the court closed the doors of federal courts to claims of partisan gerrymandering in Rucho v. Common Cause in 2019, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., writing for the five most conservative members of the court, said state courts could continue to hear such cases — including in the context of congressional redistricting.

Lawyers defending the North Carolina Supreme Court’s ruling in the new case said it was a poor vehicle for resolving the scope of the independent state legislature doctrine, as the legislature itself had authorized state courts to review redistricting legislation.

During the past redistricting cycle, state courts in North Carolina, Ohio and New York rejected newly drawn maps as partisan gerrymanders. In 2018, the State Supreme Court in Pennsylvania rejected Republican-drawn congressional districts.

But should the Supreme Court embrace the doctrine, “it would completely eliminate the opportunity to set aside redistricting maps based upon the proposition that they be some kind of a partisan gerrymander,” said David Rivkin, a federal constitutional law expert who served in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and has supported the independent state legislature doctrine.

It would also leave few remaining avenues through the courts to challenge congressional maps as unconstitutional. Partisan gerrymandering would essentially be legal, and a racial gerrymander would be the only way to lodge a challenge.

Embracing the doctrine could also end up gutting independent redistricting commissions that have been established by voters through a ballot initiative, such as in Michigan and Arizona, and limit their scope to only state legislative districts.

But a ruling favoring the independent state legislature doctrine has consequences that could extend well beyond congressional maps. Such a decision, legal experts say, could limit a state court’s ability to strike down any new voting laws regarding federal elections, and could restrict their ability to make changes on Election Day, like extending polling hours at a location that opened late because of bad weather or technical difficulties.

“I just can’t overstate how consequential, how radical and consequential this could be,” said Wendy Weiser, the vice president for democracy at the Brennan Center for Justice. “Essentially no one other than Congress would be allowed to rein in some of the abuses of state legislatures.”

The decision to hear the case comes as Republican-led state legislatures across the country have sought to wrest more authority over the administration of elections from nonpartisan election officials and secretaries of state. In Georgia, for example, a law passed last year stripped the secretary of state of significant power, including as chair of the State Elections Board.

Such efforts to take more partisan control over election administration have worried some voting rights organizations that state legislatures are moving toward taking more extreme steps in elections that do not go their way, akin to plans hatched by former President Donald J. Trump’s legal team in the waning days of his presidency.

“The nightmare scenario,” the Brennan Center wrote in June, “is that a legislature, displeased with how an election official on the ground has interpreted her state’s election laws, would invoke the theory as a pretext to refuse to certify the results of a presidential election and instead select its own slate of electors.”

Legal experts note that there are federal constitutional checks that would prevent a legislature from simply declaring after an election that it will ignore the popular vote and send an alternate slate of electors. But should the legislature pass a law before an election, for example, setting the parameters by which a legislature could take over an election and send its slate of electors, that could be upheld under the independent state legislature doctrine.

“If this theory is embraced, then red state legislatures are going to be smart, and they’re going to start to put into place these things before 2024,” said Vikram D. Amar, the dean of the University of Illinois College of Law. “So the rules are in place for them to do what they want.”

Adam Liptak reported from Washington, and Nick Corasaniti from New York.