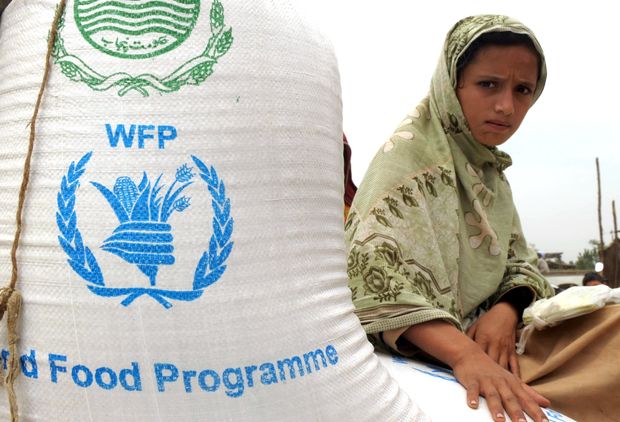

The World Food Program’s efforts to prevent hunger being used as a weapon of war were recognized in its Nobel Peace Prize on Friday.

Photo: AFP via Getty Images

The United Nations World Food Program was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts to combat hunger and prevent it being used as a weapon of war.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee said the WFP’s work toward providing food security can help to improve prospects for stability and peace, and noted how it has taken the lead in combining humanitarian work with peace efforts in South America, Africa and Asia. The committee chairwoman, Berit Reiss-Andersen, said she hoped the award would draw more global attention to the problem of hunger as the coronavirus pandemic upsets supply chains and diverts resources to stemming the spread of the infection.

“Until the day we have a medical vaccine, food is the best vaccine against chaos,” said Ms. Reiss-Andersen.

“The coronavirus pandemic has contributed to a strong upsurge in the number of victims of hunger in the world,” the committee said. The World Food Program has demonstrated an impressive ability to intensify its efforts in the face of the crisis, it added.

Ms. Reiss-Andersen also warned that the multilateralism that helped establish the U.N. and agencies such as the WFP is under threat as countries begin to go their own way—something that President Trump has been accused of for his “America-First” foreign policy, despite the U.S.’s strong financial support for the WFP.

“When you follow international debate and discourse, it’s definitely a tendency that international institutions seem to be discredited more than, let’s say, 20 years ago,” Ms. Reiss-Andersen said. “Multilateralism seems to have a lack of respect these days.”

WFP’s funding has held up better than that of some organizations, however, and has enjoyed significant backing from the U.S., which has consistently been its largest donor. Washington’s contribution in 2020, as of Oct. 3, was $2.73 billion—some 43% of the total $6.35 billion donated, WFP figures show. Germany was the next largest contributor, with $964 million. China provided $4 million.

Related Reading

Speaking to reporters after announcing the award, Ms. Reiss-Andersen described how many agencies in the U.N. network are finding it hard to get financial backing, saying there isn’t as much state support as there was in the past.

The WFP, though, is able to perform at a high level, she said, operating in countries such as Syria, North Korea and Yemen, where many other organizations struggle to gain access.

“But it is evident that the organization is dependent on funding to carry out its tasks,” Ms. Reiss-Andersen said.

In Syria, where the nearly decade-long war has left more than nine million people with limited access to food, the WFP provides monthly food assistance to nearly half of those affected. Throughout the conflict, hunger has been weaponized through the use of crippling sieges—most often by the government of President Bashar al-Assad—to force surrender. Like other U.N. agencies, the WFP has also been criticized for abiding by government restrictions on its operations in the country, particularly, in opposition-held areas, leading to accusations that it was amplifying the Assad regime’s starvation tactics.

The WFP’s largest emergency response effort at present is in Yemen, where a nearly six-year war between an international Saudi-led coalition and Iran-backed Houthi rebels has caused a humanitarian catastrophe and left two-thirds of the population, about 20 million people, food insecure. Some 10 million of them are acutely food insecure, according to WFP. The organization says two million children in Yemen require treatment for acute malnutrition, which can lead to stunted growth and affect their mental development.

This year, the WFP is aiming to provide 13 million Yemenis with food assistance either through vouchers or distributions of essentials such as flour and pulses. In more stable areas of Yemen, WFP gives cash assistance to buy food. It provides nearly a million Yemeni school children with nutritious snack bars during school hours.

Friday’s award comes as the WFP warns of the threat the coronavirus pandemic will have on the developing world, as the economic impact of the virus pushes millions into poverty and disrupts food-supply networks.

A report from the agency earlier this year warned that the pandemic has raised the prospect of “multiple widespread famines of biblical proportions.” It has estimated that the number of people suffering from hunger could almost double from 135 million to more than 250 million as a result of the disruptions caused by the virus.

The coronavirus is magnifying the challenges for WFP campaigns already operating in some of the world’s most intractable conflict zones. In war-torn South Sudan, its teams are providing food assistance to some 1.8 million people, up from 1.3 million in July. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the WFP is leading efforts to address a worsening food crisis where 22 million people are now in need of food assistance, up from 15 million people at the start of the year.

But the challenges aren’t restricted to countries at war. The number of people in hunger across Southern Africa has almost doubled over the past three months, despite the continent’s most advanced economy, South Africa, registering its second-largest grain harvest in history.

Nearly a third of Ethiopia’s population is facing a food crisis despite being on track for a record wheat and corn harvest. Zambian farmers have harvested enough corn in a single season to meet the country’s annual demands for nearly three years, but some 2 million Zambians are facing acute food shortages and chronic malnutrition.

David Beasley, the executive director of the WFP responded to news of the award by saying it was a humbling recognition of the work of the organization’s staff who lay their lives on the line to bring food assistance to close to 100 million people across the world. It also said it has to work hand-in-hand with governments and the private sector.

“Today is a reminder that food security, peace and stability go together,” he said. “Without peace, we cannot achieve our global goal of zero hunger; and while there is hunger, we will never have a peaceful world.”

Mr. Beasley previously noted in 2017 that the WFP’s efforts also boosted the U.S.’s own long-term security interests in some of the most volatile parts of the world.

“Humanitarian assistance—especially the food aid distributed by the U.N. World Food Program—is one way to combat extremists,” he wrote. “This is my message to President Trump and his friends and allies. Proposed massive cuts to food assistance would do long-term harm to our national security interests.”

In all, 318 candidates were nominated for the peace prize this year, the fourth-highest number on record. The Nobel committee doesn’t announce nominees, and doesn’t make the deliberations for the awarding of the prize public for 50 years, and then only on a case-by-case basis.

The WFP joins past winners such as Nelson Mandela and Mikhail Gorbachev, in addition to receiving a cash prize of over $1 million. Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prize in his will along with prizes for chemistry, physics, physiology or medicine, and literature. A prize for economics was created in his name. The peace prize was first awarded in 1901 and is selected by a committee in Norway’s capital, Oslo. During Nobel’s lifetime Sweden and Norway were in a union, which was dissolved in 1905.

—Raja Abdulrahim, Sune Engel Rasmussen and Joe Parkinson contributed to this article

Write to James Hookway at james.hookway@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8