Hamilton content? Hamilton content! Hardly any topic is more ubiquitous these days than Lin-Manuel Miranda’s smash musical. Fans, academics, artists and writers of all stripes – even Supreme Court justices – have found cause to analyze or drop references to it. Seemingly the only platform it hasn’t graced is SCOTUSblog.

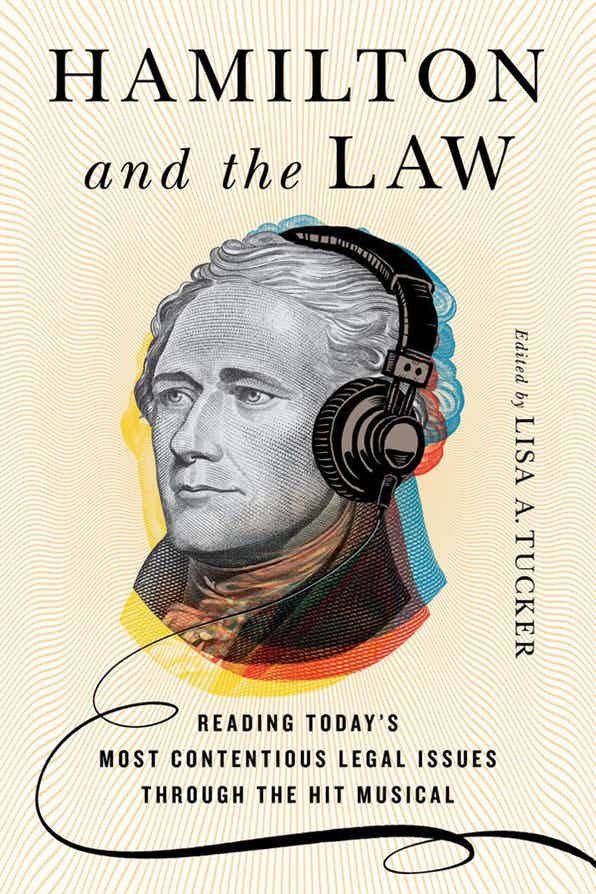

That is, until now. With Hamilton and the Law, released in October from Cornell University Press, editor Lisa Tucker has invited 32 luminaries from across the legal profession to “read[] today’s most contentious legal issues through the hit musical.” And how to discuss “contentious legal issues” without turning to the Supreme Court? While the book deals with a wide range of topics, Tucker and her compatriots – many of them respected Supreme Court advocates and scholars – spend a good deal of time gleaning lessons from the musical regarding the justices and their role in our constitutional republic.

That is, until now. With Hamilton and the Law, released in October from Cornell University Press, editor Lisa Tucker has invited 32 luminaries from across the legal profession to “read[] today’s most contentious legal issues through the hit musical.” And how to discuss “contentious legal issues” without turning to the Supreme Court? While the book deals with a wide range of topics, Tucker and her compatriots – many of them respected Supreme Court advocates and scholars – spend a good deal of time gleaning lessons from the musical regarding the justices and their role in our constitutional republic.

Lisa A. Tucker is an associate professor of law at Drexel University’s Thomas R. Kline School of Law, where she specializes in legal research and writing as well as the Supreme Court. A former contributor to SCOTUSblog, Tucker is also the author of the novel Called On.

Thank you, Lisa, for participating in this Q&A for our readers, and congratulations on the publication of your latest book.

***

Question: You recount in the preface that Hamilton and the Law was conceived on one journey, a college tour road trip with your daughter. Tell us about the journey that followed. How did you spin your idea into a successful partnership with so many contributors?

Answer: The journey that followed was both epic and unexpected. Once I started talking to lawyer and law professor friends about my idea, they were almost as excited as I was. It turned out, they were, like me, obsessed with Hamilton: An American Musical. Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson proudly told me she’d been the first federal judge to quote the musical in an opinion. Elizabeth Wydra reported that they sang it around her office and tried to fit lines from the show into their briefs. Numerous law professors taught it in their classes – even classes that had nothing to do with the Constitution or the Federalist Papers! Erwin Chemerinsky told me that he’d learned to use technology in the classroom specifically so he could share parts of the show with students.

Based on the enthusiasm of a few, I decided to try to spread the net wide. I wanted to find contributors who were truly diverse, in every way: male and female; black, white and brown; older and younger; liberal and conservative; at top-ranked law schools and at lesser-known institutions. When I posted a call for proposals on Facebook, I got more replies than I have on almost any other post; to my surprise and delight, many were from people I’d long admired but never would have dared approach. They, in turn, suggested other enthusiasts. Before I knew it – like, in a month — I had commitments from about three dozen contributors.

A scene from Drexel Law’s trial of Aaron Burr (Art Lien)

Meanwhile, at Drexel Law, we decided to try Aaron Burr for the murder of Alexander Hamilton, using only the musical’s libretto as the record. Greg Garre and Neal Katyal traveled to Philadelphia to lead the prosecution and defense teams. Ketanji Jackson judged. Local attorneys and law students “played” the witnesses. Art Lien sketched, just like he would at a SCOTUS argument. When the audience of 50 took on the role of the jury, the verdict was “not guilty” – but by a margin of a single vote. As I’d thought all along, the “evidence” in the musical points toward premeditated murder by Burr, but also toward an argument for his self-defense, perhaps even toward suicide by duel. Drawing all of that evidence out was educational and thought-provoking.

It was becoming clearer and clearer to me that this wasn’t just a gimmick or a fun idea born of way too many miles of driving between small liberal arts colleges. The musical really spoke to lawyers. It made them think more deeply about their areas of the law.

Question: As you note in your own essay in part one, “Hamilton: An American Musical does not mention the Supreme Court.” Yet a number of the book’s contributors focus entirely on the court, and many who don’t in these pages do so in their careers. Did you conceive of the book as being so court-focused? If not, why do you think it turned out that way?

Answer: I didn’t conceive of the book as being so court-focused, but I’m not surprised that a number of the essays explore the role of the court in the constitutional democracy Hamilton helped create. First, and perhaps most obviously, most of my friends are SCOTUS and SCOTUSblog junkies; that’s what they think about day in, day out. But I also think that the absence of SCOTUS in the musical gave birth to some fan fiction in the book (and if you’re into fan fiction, Rebecca Tushnet has lots to say in the book about the genre). Authors explored what was there all along, but never mentioned: how the judicial system was integral to the “notion of the nation [they] now [got] to build.” The contributors who talked about SCOTUS also reflected on how the musical might influence the court; would originalism become a more progressive idea, for example, as the musical’s portrayal of the Founding was a progressive one? After seeing the show, had the justices taken away any lessons about society, about justice?

But it’s important to emphasize, even here on SCOTUSblog, that the book has many, many other themes. Essays explore the role of race and gender in America; copyright issues inherent to the musical’s sampling of hip-hop artists’ work; domestic violence (was Maria Reynolds a victim?); dueling (the entire show is a duel, if you think about it); and much, much more.

Question: Your essay focuses on confirmation battles, specifically the bitter clash over the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh in 2018. The book was released on Oct. 15, 2020, right in the middle of the confirmation fight over now-Justice Amy Coney Barrett. How do you think Hamilton would have viewed the state of modern Supreme Court nominations?

Answer: Wow. That’s a tough one. At least in the early part of his career, I think that Hamilton would have been shocked that we have confirmation battles at all. After all, in the musical, Jefferson says he’s “already Senate-approved.” In real life, he certainly didn’t plead his case before the Senate! In the show, Hamilton is also surprised by the idea of campaigning and comments “That’s new” when Aaron Burr is making the rounds.

But I think the duelist in Hamilton would have been fascinated by the process – and, as Jody Madeira, Benjamin Barton and Ian Millhiser describe in Hamilton and the Law, duels are verbal and political as well as, in their physical form, lethally violent. This was a man who fought for his ideals. The fight would have interested and provoked him. Modes of constitutional interpretation – and that ongoing battle – would have probably inspired him to write another 51 Federalist Papers.

As for televised hearings, Hamilton would have loved those. He would have broken out his fanciest knee-length coat and cravat. He would have welcomed the chance to pontificate, either as a participant or as a commentator. And then he would have pitched op-ed after op-ed to the national papers, if he wasn’t writing exclusively for the paper he founded, The New York Post. I can just picture the letters to the editor! “Your obedient servant, A. Ham.”

Question: President George Washington reportedly considered Hamilton to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court, for chief justice no less. What kind of justice do you think Hamilton would have made?

Answer: Hamilton would have been the very opposite of a shrinking violet. If he had sat on the modern court, he would have wanted to sit between Justice Stephen Breyer and Justice Clarence Thomas (I know, it wouldn’t actually work that way) and whisper in their ears during the oral arguments. He would have peppered advocates with questions. He would have chummed around with Justice Antonin Scalia and engaged in a “duel” of sorts about who could write the most scathing dissent.

Meanwhile, he would have been furiously taking notes about everything, all the better to have his papers preserved for future scholars.

One question occurs to me, though: If Hamilton had become a justice, could he have restrained himself, as justices traditionally do, from commenting on politics? And would he ever have written the Reynolds Pamphlet? If not, just think how the course of his life would have changed.

Question: In part three, the book turns to race. Hamilton has long been thought of as ahead of the court on this issue. He promoted abolitionist causes until his death, 52 years before the court cemented slavery’s place in our antebellum Constitution in Dred Scott v. Sanford. Since the book’s publication, however, reports have emerged that Hamilton owned slaves during his lifetime. I’m curious to know how you reacted to these new findings. How do they impact the legacy of Hamilton the person? Of Hamilton the musical?

Answer: When I learned that Hamilton was himself a slave owner, I had mixed reactions. In her essay in the book, Christina Mulligan discusses the controversy that engaged many historians from the start: that the musical gives a somewhat inaccurate picture of Hamilton as an abolitionist. Certainly, the discovery that he himself owned slaves supports that view. So in that vein, it wasn’t a surprise. But I’m far from a Hamiltonian scholar; I’m just an uber-fan of the musical. Now, when I think about the Alexander Hamilton character in Hamilton: An American Musical, I feel sort of like I did when I found out that Harper Lee had written an earlier first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird and that our justice-loving, segregation-hating Atticus Finch wasn’t all that he seemed. I still haven’t been able to bring myself to read Go Set a Watchman. It’s just too disappointing.

Still, I think that slavery as a theme in the musical is an important one, for several reasons. John Laurens’ fight for racial equality is mirrored by the musical’s visual advocacy for it. The “revolution” for independence in the musical echoes the cries for equality and cohesion that we still hear today. And several of the African American actors have commented that they were meaningfully affected by the incongruity of playing white men who enslaved their ancestors. They found ways to reconcile the two; Christopher Jackson, who played George Washington in the original cast, decided to hang his head at the end of the musical when Eliza talks about his legacy. Christina Mulligan reflects in her essay in the book that “[E]ven if we understand Hamilton as fiction, it still has a profound effect on how its audience engages with the reality of the Founding era.”

Just as documentaries and news stories move us to action, so too do narratives through which audiences can connect to and empathize with those whose rights have been violated. Hamilton, by offering us front row seats to a protest which changed the course of history, even inviting us in (“Ladies and gentlemen, you coulda been anywhere in the world tonight. But you’re here with us in New York City!”), may have helped people see that they and their friends could make a difference. Otherwise, as the musical asks, “What are the odds the gods would put us all in one spot?”

As contributor Kimberly Norwood describes in the book, the musical is a protest, both on its face and just beneath the surface, through the story that it tells and the way that it tells it.

A hip hop musical? People of color playing the roles of the Founding Fathers? A focus on the Founding Mothers’ role? “You must be outta your goddamn mind!” A protest against Broadway conventions, the musical emphasizes the importance of protest as a legacy that the Founders, who fought against oppression, left for our generation. A protest against conventional stories in which the “hero” comes out victorious and the “villain” gets his just deserts, Hamilton asks us to consider if there are real “winners” in a war, or whether war – actual or political – is destined to scar those who participate. A protest against the history books, Hamilton’s Founders, all people of color, earn the audience’s support and empathy; the white people receive its scorn.

When our children tell the story of the Founding, they will tell the story of Alexander Hamilton and his posse. But learning that story through the musical means that they will tell a story that America has not often heard, or at least not often listened to carefully. And perhaps the musical will encourage them, however indirectly, to engage in protest about things that really matter.

So, does it matter that the real Alexander Hamilton was a slave owner? In the context of history, yes, absolutely. In the context of the musical, I’m not as sure.

Question: Immigration is another focus of the book, in part five. Most immigration policy today comes not from Congress but from the White House, and in recent years the court has grappled extensively with dueling executive orders from Presidents Obama and Trump over everything from children brought here without documentation to a travel ban and border wall. An immigrant himself, Hamilton repeatedly called in the Federalist Papers for a powerful executive, remarks which are quoted often by the justices in their opinions on the separation of powers. What do you think Hamilton would have made of the expanded role of the president on immigration, and of the court’s grappling with it?

Answer: The Hamilton in the musical believed strongly that immigrants were an essential part of the fabric of America. “Immigrants, we get the job done!” is the most applauded line in the show. And, as Neal Katyal writes in the book, “[That line], and Hamilton as a whole, can be understood as an even stronger dissent to the Supreme Court’s majority in Trump v. Hawaii,” the court’s 2018 decision upholding Trump’s travel ban by a 5-4 vote. He goes on to say, “In writing Hamilton, [Lin-Manuel] Miranda understood the way in which our Founders celebrated, and did not demonize, immigration.” Katyal remarks, “I am a deep believer in the power of art to bring people together.”

But to some extent, of course, Hamilton is art, and Miranda took dramatic license when creating Alexander, the character. By 1800 or so, the real Alexander Hamilton had lost his enthusiasm for vigorous and unfettered immigration. As Ron Chernow put it, “Throughout his career, Hamilton had been an unusually tolerant man with enlightened views on slavery, Native Americans, and Jews. His whole vision of American manufacturing had been predicated on immigration. [By the turn of the 19th century], embittered by his personal setbacks, he sometimes betrayed his own best nature.”

In Federalist No. 70, Hamilton says that “[e]nergy in the Executive is a leading character in the definition of good government. It is essential to the protection of the community against foreign attacks.” Note the use of the word “attacks”; Hamilton apparently wasn’t concerned about the immigration of foreign citizens, but only about attacks by them. And he loved the idea of a strong president, at least in some realms.

As for the court? Well, Hamilton tells us in Federalist No. 78 that the judicial branch has practically no power, particularly when compared to the executive:

Whoever attentively considers the different departments of power must perceive, that, in a government in which they are separated from each other, the judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution … The Executive not only dispenses the honors, but holds the sword of the community. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.

So I’m not sure he would have been impressed with the court telling the president that his immigration policy was for the birds, if and when it ever did so.

In short, Hamilton would have supported the concept of the executive branch enforcing national policy, and he probably would have opposed policies for expansive immigration. Still, given his deep sense of justice, he would likely have encouraged citizens to resist demagoguery.

And all of this might be wrong. All we’ve got are the words and ideas he left behind. As the Hamilton of the musical put it, “Uh, do whatever you want. I’m super dead.”

Question: A broader question to end on. Hamilton the musical is successful in part because it embraces the political. It reimagines a story about white men as one with an equal focus on women, told through hip-hop by a cast of actors who are predominantly Black, Indigenous or People of Color. The Supreme Court, on the other hand, struggles enormously to avoid the appearance of engaging in politics, while issuing rulings every year that transform the political landscape. Do you think that effort is sustainable? If not, are there lessons from Hamilton the justices should heed?

Answer: I think that, until quite recently, the justices definitely agreed with Aaron Burr that “talk less, smile more” was the way to go. I’ve often heard the justices comment that their opinions speak for them; their job is not to comment on the impact their decisions will have on American society. Still, I think the most important words in your question are “the appearance.” Until now, much of the American public, even educated members of it, would have described the court as politics-free, because the workings of the court have been so closely guarded and veiled in secrecy. Insiders have always known better. There has always been a political fight going on in the marble palace; it just rarely poked its head out the bronze front doors.

What I think we are seeing now is that door being opened. Before her death, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had quite a lot to say about the abject politics of the court. A few days ago, Justice Samuel Alito gave an unquestionably political (and combative) speech to the Federalist Society. A few years ago, when it was reported that leaks had emerged about the Affordable Care Act case, I at first told friends not to believe it; leaks didn’t happen from the Supreme Court. I was wrong, at least prospectively. And the confirmation battles: Merrick Garland, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, Amy Coney Barrett – these have laid the political nature of the court bare for all to see.

The next step, I think, in maintaining appearances, will be through writing even more carefully crafted opinions than ever. To convince a public that increasingly cares about the court that the institution is apolitical, the justices will gird their opinions with empirical as well as legal support. And if, as some predict, individual liberties begin to fall, I think the public will engage directly in the political process that chooses Supreme Court justices and vote out those who manipulate or obstruct it.

Hamilton: An American Musical teaches, “You have no control: who lives, who dies, who tells your story.” As Professor Anthony Farley describes in Hamilton and the Law, judges and justices tell stories when they write majority opinions. Often, those in the dissent tell a very different version of the story. Litigants can’t control those narratives, and they are essential to outcomes. From a meta perspective, history will tell the story of this stormy period of Senate and court politics and rights-bartering.

So, the most important lesson the justices should heed? “History has its eyes on you.”

Recommended Citation: Kalvis Golde, Ask the author: Hamilton and the Law (and the court), SCOTUSblog (Nov. 25, 2020, 4:05 PM), https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/11/ask-the-author-hamilton-and-the-law-and-the-court/